The Eternal Gardener

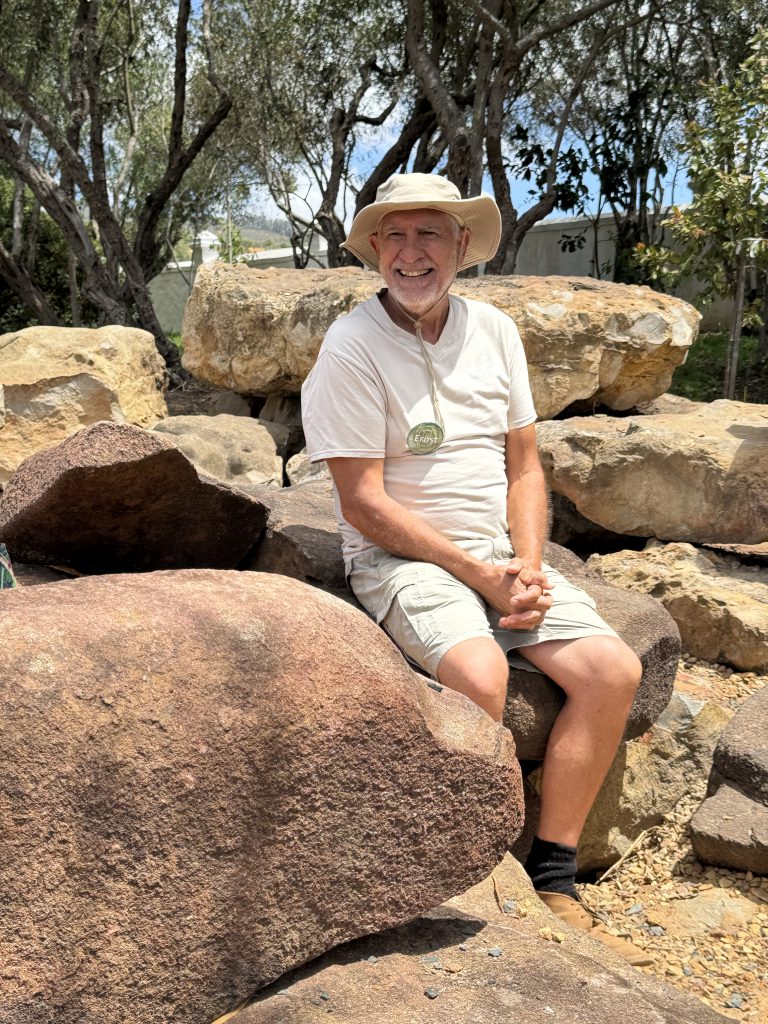

February 29th, 2024Behind Babylonstoren #4: Dr Ernst van Jaarsveld

“Everything starts with stone. Stone becomes soil. The better your soil, the better you eat.” So says Dr Ernst van Jaarsveld, renowned horticulturist who spent 42 years at Kirstenbosch Botanical Garden in Cape Town where he planted and curated the Botanical Society Conservatory, before joining Babylonstoren on his retirement in 2015.

“I’m fortunate that the owner here doesn’t hold my age against me,” smiles Ernst. Guests and employees alike are most fortunate to benefit from Ernst’s tremendous knowledge of indigenous plants, coupled with his passion for sharing what he knows. Growing up in Pretoria, he recalls being crazy about insects and frogs from a young age. “That’s where it started. When students arrive on the farm, I can immediately see who has it – this natural affinity for plants and nature,” he says.

On Mondays and Fridays from 11h30 to 13h00 Ernst leads guests on a specialist tour, starting with Babylonstoren’s 5 ha fruit and vegetable garden. “The garden provides a tangible metaphor for the history of South Africa. It is a practical way of telling our story,” he says. The garden layout is based on the Company’s Garden established by Jan van Riebeeck at the Cape. The spice trade shaped what South Africa would become, as it created the need for fresh fruit and vegetables at the Cape. The Spice House at Babylonstoren is a verdant ode to this chapter in the country’s history, with a spice collection that includes ginger, turmeric, and curry leaf, amongst others.

Besides growing food for passing ships, Van Riebeeck was also tasked with identifying and collecting useful indigenous plants to ship back to Europe. Ernst’s area of focus is the indigenous garden, called the Garden of the San, in honour of the indigenous tribes of the land. “People don’t always consider the impact plants have on human development,” says Ernst. “The Khoi and San tribes were nomads who didn’t practise agriculture. Black tribes never settled in the Western Cape as their sorghum grain couldn’t survive here due to a lack of summer rainfall.”

Construction of the Succulent House began in 2016, along with the neighbouring Clivia House. Every inch of the long, rough-hewn wooden structure is lined with beautiful organically shaped clay containers in varying sizes, filled with roughly 3500 plants. He is particularly passionate about Gasteria (ox-tongue or beestongetjie), Mesembryanthemaceae (mesembs or vygies) and Crassulaceae (stonecrop or plakkies) and prefers to water the vast succulent collection himself. “Watering is an art. If you don’t know what you’re doing, you’ll skip something. We have plants from summer and winter rainfall areas in close proximity, so you must know when to pause and when to move on. Some plants need water stress to flourish,” he adds.

Ernst was joined by an assistant horticulturist, Cornell Beukes, in 2022. They regularly go on veld expeditions to collect rare plant and rock material. “We went to the Limpopo recently to look for Sand River Gneiss rock that is 3.3 billion years old. It is of the oldest rock on the planet and a remnant of the Earth’s old crust,” says Ernst. The two share a deep love for the natural world, from plants and rocks, to fish and geckos.

“More than a mentor and a colleague, Oom Ernst is a great friend to me,” says Cornell. “It goes without saying that I’ve learnt a huge amount about succulents from him. There are few things that give me greater joy than seeing Oom Ernst’s excitement when we finally find the plant that we scaled mountains for. To be a part of this journey with him, to share in the enthusiasm and laughter in the middle of nowhere, it’s an incredibly special feeling. But the greatest lesson I’ve learnt form Oom Ernst is to be grateful and calm – everything will happen in its own time. This is so true and it is a belief that has opened many doors, also in my own life,” says Cornell.

In the Welwitschia Garden that he started planting during the pandemic, Ernst points out a dry welwitschia trunk and mentions that it is 250 years old. “You cannot transplant a welwitschia plant and we had to sow seed, of which the oldest is now about two years old.” A second later he spots a tiny girdle-tailed lizard (Cordylus cordylus) dashing over a rock, before bending down to tug at a weed. “I never stop weeding,” he says. He describes his purpose as a gardener as threefold: for pleasure, education, and research purposes.

A short distance from the Welwitschia rock garden lies the rock gong. A collection of dolerite iron rocks from the Karoo, placed on a 30-ton base of silcrete stone transported to the farm from Fisantekraal. To the untrained eye it resembles a grouping of large, dark rocks. As Ernst strikes each rock, different notes ring out. “This is the oldest instrument know to humanity. Wherever dolerite can be found, archaeologists have found remnants of rock gongs that were used for percussion,” he says.

In a society that does not necessarily prize the passage of time, and in an era obsessed with immediate gratification, many hesitate to plant a tree or a garden that will only be fully grown long after their own life cycle has ended. “Yes, that is how some see it,” he says. “But garden work never stops. You plant for the future. Life carries on without us. Gardening is a means to immortality.”

Besides the specialised tours on Mondays and Fridays from 11h30 to 13h00, Ernst also presents 10–12 workshops per year on a variety of topics, like waterwise gardening and biological pest control.